Scientific evidences claimed by experts

- FledglingsNotConvicts

- Mar 2, 2019

- 9 min read

Updated: Mar 11, 2019

Experts indicated the evidences why children as young as 12 should not be exposed to the criminal justice system.

According to Unicef, “Lowering the age of criminal responsibility is an act of violence against children. Children who are exploited and driven by adults to commit crimes need to be protected, not further penalized. They should be given a second chance to reform and to rehabilitate.”

The Disadvantaged Environment and Profile of the Filipino Child in Conflict with the Law (CICL)

The typical CICL is poor, lacking in education, a victim of parental neglect and/or abuse, and lives in a criminogenic environment. These clearly place the young person at a disadvantage, making deficiencies in decision-making and vulnerability to coercion all the more pronounced. To place such a young person, already victimized, into the hands of the criminal justice system further curtails his or her future prospects, and pushes them further towards a negative life trajectory.

The aforementioned characteristics of youth indicate that they are less capable than adults—even at age 15, but most certainly at age 12—to behave in accordance with what they may discern or know to be right versus wrong action. Although transitory, these developmental limitations are not under the volitional control of the young person.

Moreover, adolescence is still a time of self and identity development, and antisocial behaviors do not reflect “criminal identity” at this stage. Research indicates that most youth abandon antisocial behavior at the time that they exit adolescence, and that only a minority persist s in criminal behavior as a function of pervasive neurological and environmental risk factors. In fact, exposure to the criminal justice system, where the child will be labeled a criminal and where he or she is exposed to criminal models, will more likely establish the “criminal identity” of the young person. Studies have shown that encounters with the adult justice system results in greater subsequent crime, including violent crime, for the juvenile.

The PAP reiterates its position against the lowering of the minimum age of criminal responsibility from 15 to 12 years old. We urge the government and relevant stakeholders to

Implement restorative justice and appropriate interventions for our CICL. CICL should experience sanctions in community and family settings whenever possible, especially for first and nonviolent offenses. They should be excluded from the adult criminal system and given full opportunities to develop into responsible adults who can make meaningful contributions to society.

A review of position papers crafted by medical experts, economists, social workers, and childrens’ rights group showed there were risks posed to children at 3 stages:

Before a child may commit a crime.

During a child’s stay in a youth detention center – known as Bahay Pag-Asa (House of Hope) – or worse, a jail.

After a child leaves a rehabilitation center or jail.

1. Before a child may commit a crime, he/she is already vulnerable

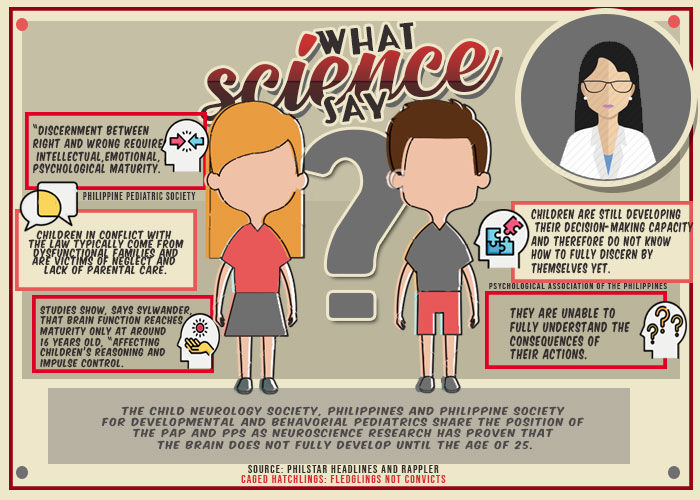

According to the Psychological Association of the Philippines (PAP), this means that changes in areas of the brain, which are responsible for impulse control, decision-making, regulating emotions, and evaluating risks and rewards are still taking place. Unlike adults, children are less able to consider and understand the long-term consequences of their actions.

“Discernment between right and wrong requires intellectual, emotional, and psychological maturity. This is a tall order for children who are still in the process of developing in all aspects,” the Philippine Pediatric Society (PPS) said. “Younger children, therefore, need protection from the law and should not be held criminally responsible for their actions.”

“The developmental immaturity of young people mitigates their criminal culpability. Although they may be able to discern right from wrong action, it is their capability to act in ways consistent with that discernment that is undermined, given the following characteristics at this stage.

As minors, young people lack the freedom that adults have to assert their own decisions and extricate themselves from criminal situations.

"To place such a young person, already victimized, into the hands of the criminal justice system further curtails his or her future prospects and pushes them further toward a negative life trajectory.” -PAP

Furthermore, Dr. Liane Peña Alampay said “ It imperils the children's future if they undergo the criminal justice system. If society labels them as a criminal or a delinquent, they will own it. It is also the reason why teenagers go through a rough patch because their ability to plan and to think rationally is still developing. What they need is good quality parenting. They must feel protected, that they are not exposed to violence in their communities. “

The United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (Unicef), citing studies, said "adolescents’ brain function reach maturity only at around 16 years old, affecting their reasoning abilities and impulse control."

The Child Neurology Society, Philippines and Philippine Society for Developmental and Behavorial Pediatrics share the position of the PAP and PPS as neuroscience research has proven that the brain does not fully develop until the age of 25.

2. The Disadvantaged Environment and Profile of the Filipino Child in Conflict with the Law (CICL)

According to the PAP, brain and moral development can be delayed by cultural and social disadvantages such as poverty, exposure to crime and violence, abuse, and neglect. A situational analysis of CICLs completed by the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Council (JJWC) said that a majority of offenses where children were involved – theft and physical injury – were often related to poverty. The JJWC is tasked with overseeing the implementation of the Juvenile Justice Welfare Act (JJWA).

The typical CICL is poor, lacking in education, a victim of parental neglect and/or abuse, and lives in a criminogenic environment. These clearly place the young person at a disadvantage, making deficiencies in decision-making and vulnerability to coercion all the more pronounced. To place such a young person, already victimized, into the hands of the criminal justice system further curtails his or her future prospects, and pushes them further towards a negative life trajectory.

The aforementioned characteristics of youth indicate that they are less capable than adults—even at age 15, but most certainly at age 12—to behave in accordance with what they may discern or know to be right versus wrong action. Although transitory, these developmental limitations are not under the volitional control of the young person.

Moreover, adolescence is still a time of self and identity development, and antisocial behaviors do not reflect “criminal identity” at this stage. Research indicates that most youth abandon antisocial behavior at the time that they exit adolescence, and that only a minority persist s in criminal behavior as a function of pervasive neurological and environmental risk factors. In fact, exposure to the criminal justice system, where the child will be labeled a criminal and where he or she is exposed to criminal models, will more likely establish the “criminal identity” of the young person. Studies have shown that encounters with the adult justice system results in greater subsequent crime, including violent crime, for the juvenile.

The PAP reiterates its position against the lowering of the minimum age of criminal responsibility from 15 to 12 years old. We urge the government and relevant stakeholders to implement restorative justice and appropriate interventions for our CICL. CICL should experience sanctions in community and family settings whenever possible, especially for first and nonviolent offenses. They should be excluded from the adult criminal system and given full opportunities to develop into responsible adults who can make meaningful contributions to society.

3. Not enough rehabilitation centers to help children

The proof against lowering the MACR becomes even clearer when reviewing the condition of majority of Bahay Pag-Asa centers. While lawmakers claimed that lowering the MACR from 15 to 12 was intended to protect children, they failed to listen to the JJWC itself.

In this article, it is entirely focused on “Bahay Pag-asas” and what it truly is despite having a farce of being a 24-hour youth care facility.

What is a “Bahay Pag-asa” you may ask? Those said centers are youth care facilities made to offer rehabilitation and to stage an intervention to the children who is conflicted with the law, this is also mandated by the law themselves.

For there are only 63 Bahay Pag-asa facilities nationwide and five of which are no longer operating. Due to the lack of these facilities some children would be sent to jail with the adults.

Most people would envision the “Bahay Pag-asas” as a way to prevent a child offender to further their crimes.

On the other hand, others say that the law does not need to be changed nor added even more, for it is based on how strong the law would be implemented instead. This is also supported by the President of Ateneo de Manila University, Fr. Jose Ramon Villarin.

With the House Proposal, the Social Welfare department became in charge of this establishment, providing its funds and managing the “Bahay Pag-asas” instead of the local government, and that they have also taken the blame for the poor condition of the youth care facilities.

People from the bill had also hoped to launch two or more than agricultural camps within Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao, one of each. The idea is also similar with the “Bahay Pag-asa”, where children would be confined instead being sent to jail.

This is also mandated for the confinement of convicted children in agricultural camps or other youth care facilities.

Even the Human Rights Commissioner, Leah Armamento said that the existing facilities that are similar to the “Bahay Pag-asa” is not up to the criteria of it. She had also stated that the “Bahay Pag-asa” itself is not suited for restoring the justice this country of ours once had.

Senator Pangilinan also said that only around 40 out of 81 provinces with “Bahay Pag-asas” have centers.

This proves that this law has not been funded properly, despite the fact there is money provided yet it is placed for self-serving interests with the people who can control the said money for funding the “Bahay Pag-asas”.

Back then, in the year 2013, funding for these facilities was only assigned to a team of child experts, as to when the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Center amended to mandate children with a range of 12 to 15 who would commit serious crimes to be sent to these facilities.

Año had also spoken to the senators that the Department of the Interior and Local Government would order local government units (LGUs) to be able to establish “Bahay Pag-asas”, as required by the law.

However, the executive director, Tricia Oco, said that the law only allows the national government to provide P5 million for the funding of these facilities.

Under the influence of the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act, LGUs and the national government should give P5 million for every youth care facility. Back in the 2012 amendment had also gained with a whopping P400 million for the construction of the “Bahay Pag-asas” in the provinces and cities.

In one of the previous Senate hearing, most of these youth care facilities do not match with the requirements set out by the law and that some of these facilities are even “worse” than prisons.

One of the psychologists from the PAP, Dr. Liane Alampay, pointed out that most of the “Bahay Pag-asas” do not have reformative programs for the children inside of the facilities.

They also lack the budget to equip the “Bahay Pag-asas” with social workers.

Now it is under the law that “Bahay Pag-asas” should have a multi-disciplinary team made of a social worker, a psychologist/mental health professional, a medical doctor, a educational/guidance counselor and a Barangay Council for the Protection of Children member.

Data from the Ateneo de Manila University Human Rights Center showed only 4% of LGUs appointed licensed social workers. Meanwhile, only 53% of LGUs have allocated 1% of their internal revenue allotment to strengthen local councils to protect children.

According to Human Rights Watch, visits to a Bahay Pag-asa in Manila showed the facility was poorly run and maintained.

"Water from the toilet leaked to the floors where dozens of children were sleeping, rust covered fenced cages in which children were locked up throughout the day, ventilation was poor, and many of the children had clear signs of skin infections, suggesting poor diet and sanitation," the group said in a statement.

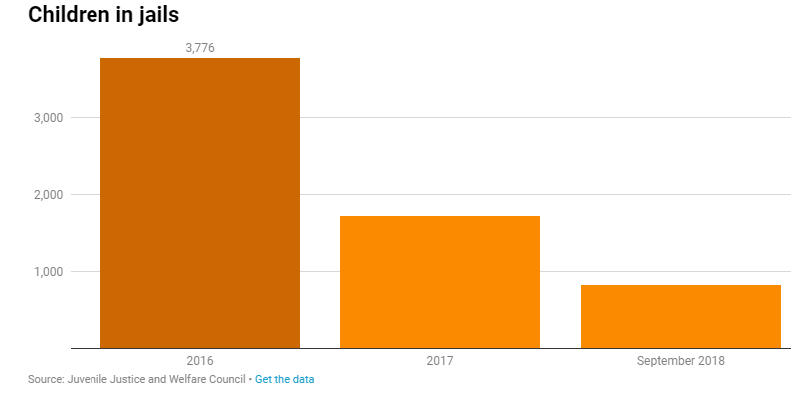

This lack of rehabilitation centers has led to many CICLs being detained in regular jails and detention centers along with adults. While numbers have gone down through the years, more than 800 children were still in jails as of September 2018 – despite restrictions imposed by the JJWA.

4. Stigmatizing CICLs

“Lowering the age of criminal responsibility has the effect of bringing more children into contact with the criminal justice system, increasing the rate of incarceration and aggravating the risk of recidivism,” Pais said.

JJWC policy and research officer Jackielou Bagadiong earlier denied that the current law lets children get away with crimes they committed.

“The child still has this liability but we don't detain [him or her] because given the current state of our jails, it wouldn't be possible, it would harm our future generation if we do that,” Bagadiong said during the child protection summit in 2018.

Despite of the scientific research and evidences regarding the lowering MACR, the senate justice committee who approved the house bill 8858 seems to ignore the evidences and based their decisions through their own hypothesis. Lowering MACR only shows that they failed to implement the law in protecting the children.

Source: https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/222628-reason-experts-strongly-opposing-lowering-minimum-age-criminal-responsibility?fbclid=IwAR18WaoG673DfbDTYkIShIrl4RXFvwRrfIgWOutx2cam8ABHGHaT11A8bmk

Other References:

Adhikain Para sa Karapatang Pambata (2004). Research on the situation of children in conflict with the law in selected Metro Manila cities. Quezon City: Save the Children (UK)-Philippines.

Alampay, L.P. (2006). Risk factors and causal processes in juvenile delinquency: Research and implications for prevention. Philippine Journal of Psychology, 39(1),195-228.

Alampay, L.P. (2005). A rights-based framework for the prevention of juvenile delinquency in Philippine communities. Manila: United Nations Children’s Fund.

MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Adolescent Development and Juvenile Justice. http://www.adjj.org/content/index.php

Steinberg, L., & Scott, E. (2003). Less guilty by reason of adolescence: Developmental immaturity, diminished responsibility, and the juvenile death penalty. American Psychologist, 58(12), 1009-1018.

Steinberg, L., & Haskins, R. (2008). Keeping adolescents out of prison. Policy Brief, the Future of Children, Vol. 18 No. 2, 1-7.

University of the Philippines Center for Integrative and Development Studies-Program on Psychosocial Trauma and Human Rights and Consortium for Street Children. (2003). Painted Gray Faces behind Bars and in the Streets, Street Children and the Juvenile Justice System. Quezon City: Author.

Comments